7-Eleven hot wings hurt, but it’s a good kind of hurt. So when the craving hits, I strap on my mask and walk down the block to the billion-dollar bodega to make some culinary mistakes.

Listen, security follows me in stores. It happens every 2-3 days without fail. But this guard was beyond. He followed me from aisle to aisle making direct eye contact, staring into my soul.

Of the many scourges of racism, being followed in a 7-Eleven ranks low. But when a virus is laying waste to scores of people while the economy craters and Americans are looking for someone to project their fears on, black people intrinsically know we’re going to suffer. So when an overzealous, non-black security guard is in my poultry-pining grill, I get anxious, worried he’ll escalate the situation.

In L.A., I’ve been asked to leave stores just for walking in. I’ve been completely ignored or overcharged at restaurants with what feels like a black tax. I’ve been screamed off a bus when a driver thought I’d stolen my student bus card, and I’ve been followed in retail shops as a matter of course. Once again, these incidents aren’t on racist par with mandatory minimums, redlining, being fired without cause, or getting beaten by police, but they have a cumulative effect.

We’re also reminded time and again that there’s little punishment for prejudice. Hell, there’s rarely even acknowledgment. In 2015, the LAPD dismissed 1,356 racial profiling complaints, with then-Los Angeles Police Commission President Matt Johnson stressing there’s no way to effectively gauge officer bias. Crazy how that works.

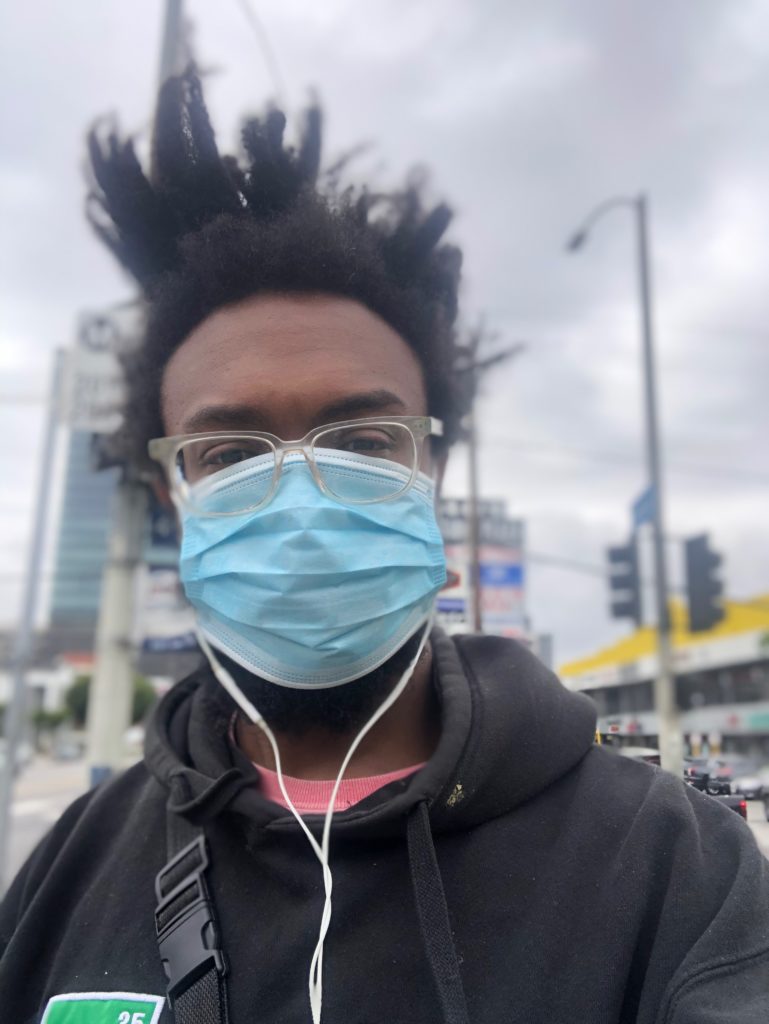

Now, in the midst of a global pandemic, wearing a mask makes this 10 times worse. You know folks are wary of you ’cause you’re a giant black person with civil-rights hair, and now you’re covering your face. Sounds like a great way to get hurt to me, and it turns out I’m not alone.

Two black men went viral after posting what they say is a video of them getting kicked out of a rural Illinois Walmart for wearing protective masks. One of the men, Jermon Best, told a local news outlet they posted the video to “shine some light because this happens so often.” In Miami, Dr. Armen Henderson, an internal medicine physician with the University of Miami Health System, says he was detained in front of his home while loading supplies for unsheltered people.

Both incidents ended without violence, but I can’t help but worry that it’s not so much a matter of if but when a terrified bigot causes irreparable harm to a black person in a mask. And that’s not the only thing that worries me or those I spoke with.

L.A.-born, Oakland-based artist and scholar Mia Boykin is back in Los Angeles during the pandemic. She worries that because her mask is made of bandana material, it could be mistakenly associated with gangs, a point echoed in this poignant Washington Post piece. She also highlights a different but related type of public haranguing black folks deal with: people invading our personal space.

“Black people experience either hypervisibility or invisibility,” she says. “I find that when I go shopping, [people] will act like I’m not there and won’t abide by the six feet social distancing rules. So I spend most of my time dodging people and trying to claim as much space as possible and being very clear about my physical movement so as not to be touched by people or near anyone.”

This point is particularly prescient when you consider that black people are contracting and dying from COVID-19 at disproportionately high rates. CDC data indicates that despite accounting for 13% of the population, 30% of COVID-19 patients are black. In Los Angeles County, 17% of COVID-19 deaths as of early April were black patients, even though black people make up 9% of the county’s population. Someone standing too close could have dire, fatal consequences— yet another risk for a community besieged by health problems caused by generations of institutional neglect.

Meanwhile, East Hollywood-based party promoter Marcel Hill has the opposite experience. He says he gets glared at in shops and avoided in the streets, a one-two punch of prejudice.

“It wasn’t until I went to my local grocery store and started noticing certain ethnic groups staring at me in a way I hadn’t noticed before. It was the type of stare that you could feel in the back of their mind was like, ‘Is he wearing the mask because of COVID-19 or is he going to try and steal something or rob the place?'” he said.

At the same time, following media reports of the virus’s outsized impact on black communities, Hill says he’s noticed people “jumping out of their way” to avoid him “as if they knew I had coronavirus because I’m black.”

“I think the problem with that narrative is not that some things can be true, it’s that it gives people who already have a ‘certain’ feeling about black people a pass or an excuse to discriminate against black people under the disguise of COVID-19,” he explained.

All these things have happened to me, too. The leaping, the staring, all the greatest hits of insidious bigotry. Whatever, I’m still gonna get those wings, even if they do taste like breaded table salt. It would just be so sick to walk into a business I’ve patronized some 30-40 times and be treated with respect every time, knowing I won’t be subjected to the nauseating trio of derision, suspicion, and supervision.

Walking while Black is already a health hazard. This pandemic only ratchets up the physiological and psychological malaise we’re sadly used to. Is there a vaccine for that?