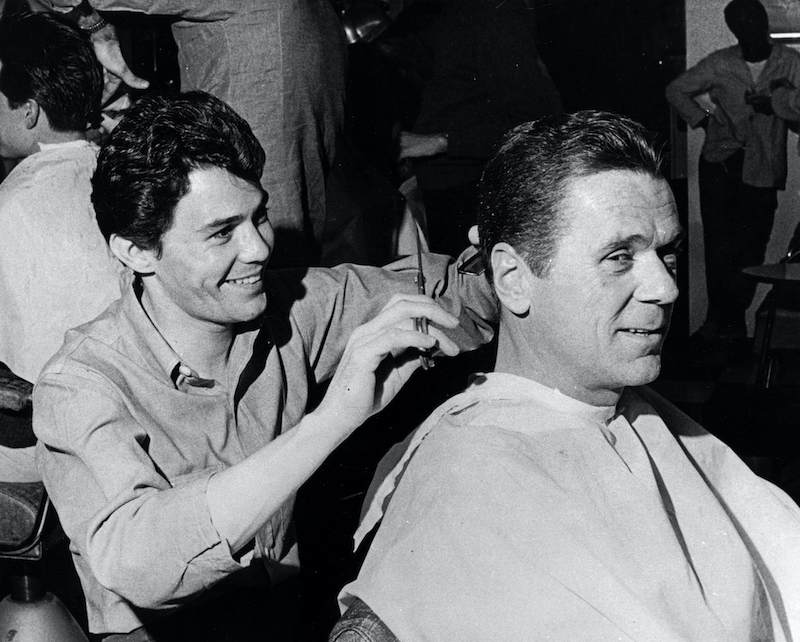

If you were one of Hollywood’s leading men in the 1960s, Jay Sebring was the stylist you wanted to cut your hair. His clients included Marlon Brando, Steve McQueen, Frank Sinatra, Warren Beatty, Bruce Lee, and Paul Newman. He gave The Doors frontman Jim Morrison his shaggy “Alexander the Great” locks. He was a pioneer of men’s hair, a Navy vet who dreamed of elevating utilitarian cuts into iconic styles and then made it happen in his own salon at 725 N. Fairfax, on film sets, and beyond.

But Jay Sebring isn’t always associated with his success or cultural legacy. The sum of his life is often overshadowed by its final moments, when he was murdered by Manson Family members Charles “Tex” Watson, Patricia Krenwinkle, and Susan Atkins on August 9, 1969, at the Beverly Hills home of his close friend and former girlfriend, Sharon Tate. He was 35 years old.

Tate was the wife of filmmaker Roman Polanski, who was in Europe at the time of the murders. She was a beautiful, young actress, weeks away from delivering her first child. In media coverage, headlines often described the victims as “Sharon Tate and 4 Others.” Those others were Sebring; Polanski’s friend, Wojciech Frykowski; Frykowski’s girlfriend, coffee heiress Abigail Folger; and Steven Parent, who was killed while attempting to leave after visiting the home’s caretaker.

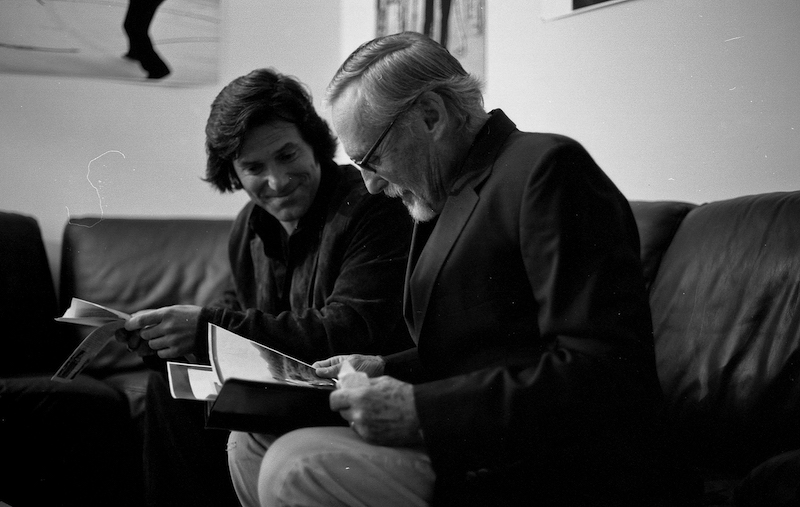

“Four others” is a phrase that sticks with filmmaker Anthony DiMaria, whose documentary Cutting to the Truth attempts to dispel rumors about the murders while painting a holistic picture of Jay Sebring. Sebring was DiMaria’s uncle, his mother Peggy’s oldest brother.

While DiMaria was just three years old when Sebring died, he remembers that Sebring would visit his family at their home in the Las Vegas area. His parents had moved there from Detroit in 1965 to work at a salon in Caesars Palace, with plans to ultimately work for Sebring in California. DiMaria says his memories of his uncle aren’t “vast, but they are indelible.” In particular, he recalls chasing one another around the yard.

“He didn’t seem like an adult, the way he interacted with me. I certainly don’t think I understood him as my uncle. He seemed more like my cool friend. It’s hard to describe, but that’s really the impact he had on me,” DiMaria said.

A few years later, DiMaria was browsing a family photo album as his mother did the laundry. He came across a picture of Sebring and remembered him right away. Excitedly, he asked his mother when they might see him again.

“I saw a pain in her eyes that I don’t think any kid is used to seeing his mother or father go through,” DiMaria said. “It wasn’t like she was sobbing or crying, but I saw something, even at that age, that disturbed me to the core that I would somehow cause my mother this type of pain.”

From that moment on, DiMaria had an urge to know more about Sebring, and it’s a feeling that never left. He’s not sure if it would have ultimately faded had there not been dozens of reminders, year after year, in tabloids, TV shows, movies, songs, documentaries, and even on T-shirts depicting the people who killed his uncle and their infamous crimes. Or, had his family not been compelled to attend numerous parole hearings, where they sit alongside other victims’ loved ones and “remind everybody who the victims really are.”

“There’s something about being a family that has been impacted by a violent crime, a murder. But also, what would normally be a personal private tragedy among the family, these murders were different. They were so notorious that they were played out on platforms and narratives as a form of entertainment,” DiMaria said.

Charles Manson, who died in 2017 at 83, and his so-called followers have been characters in South Park and American Horror Story, and in countless nonfiction and fiction interpretations of the murders. Some are musical adaptations. Other are alternative histories. They range from low-budget, poorly-rated exploitation schlock like Honky Holocaust (2014), in which Manson successfully pulls off his ‘Helter Skelter’ race war, to Quentin Tarantino’s award-winning Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2019), in which (spoiler alert) the murders never happen.

Wanting to find out who a deceased family member was isn’t so odd, especially if you never got the chance to know them. But DiMaria also sought to untangle all the bizarre rumors that surrounded Sebring, especially in the period after his death.

Media, in an effort to figure out why the Polanski-Tate home had been targeted, rushed to paint the victims as “freaky”—into the occult, drugs, orgies, BDSM, and other taboos or counterculture that, by today’s standards, are fairly vanilla. (I won’t link to them, but “exposés” into the victims’ supposed secret lives can still be found in tabloids today.) In truth, Manson directed his followers to the home on Cielo Drive because Terry Melcher, a music producer who didn’t sign him, once lived there. It didn’t matter to his followers that Melcher had since moved. They were there to kill everyone inside the house and that’s what they did.

This victim-blaming is something you’ll see today if you scroll to the comment section on any news story about someone who’s been harmed. “Why were they out so late?” “Were they drinking?” “Why were they wearing that?” “Where were the parents?” “I heard they have a criminal record.” There’s something about pinning violence on the victim’s real or imagined behaviors that makes us feel safer, as though we’re putting a barrier between what happened to other people and what certainly won’t happen to us. It also allows us, in some ways, to guiltlessly enjoy the great money-maker that is true crime.

“There’s a formula to the exploitation of notorious, sensational true crime and the first thing you have to do is strip the victims of their humanity,” DiMaria says. “They’re not like you and me; they’re not a real human being.”

To find the real, human Sebring, DiMaria talked to his uncle’s friends, former colleagues, and exes. He talked to his own family members. He pored over documents obtained from the District Attorney’s office, using autopsy reports to piece together Sebring’s final moments.

You might be surprised to know that DiMaria’s family also had three meetings with Quentin Tarantino regarding Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. In the final meeting, Tarantino completed an interview that appears in Cutting to the Truth. DiMaria said he was impressed with Tarantino and producer Shannon McIntosh because they treated Tate (played by Margot Robbie) and Sebring (Emile Hirsch) as people—something, he says, that rarely happens.

Cutting to the Truth is as much about Jay Sebring as it is about DiMaria’s journey to know him. In the end, DiMaria says he learned there were two Jay Sebrings: the man who lived, and the man who died. To tell Sebring’s story, he had to dissect the mythology, folklore, gossip, and subtext. And underneath it all, he found that Sebring’s story isn’t just a tragic tale or a salacious crime saga, but an “inspiring, glorious” story about a person who, like many before and after, came to L.A. with a dream.

As for DiMaria, he says he used to want to “kick someone in the teeth” when he saw them sporting a Manson shirt or tattoo (yes, people really get those).

“But through this process, I’ve known that Jay’s story will finally be told [and] I don’t have those feelings anymore,” DiMaria said. “Because I know for once, after 51 years, there will be knowledge of Jay with human dimension.”

Cutting to the Truth is available on streaming platforms, including Apple TV and Amazon, September 22. See the trailer below.

Juliet Bennett Rylah is the Editor in Chief of We Like L.A. Before that, she was a senior editor with LAist and a freelancer for outlets including The Hollywood Reporter, Playboy, Los Angeles Magazine, IGN, Nerdist, Thrillist, Vice, and others.