The Mayfair Hotel and the Hotel Figueroa were both built in 1926. The glamorous Mayfair played host to the Academy Awards’ first afterparty, while Hotel Figueroa was founded by the YWCA and offered lodging to women travelers, something that was relatively rare in those days. Both hotels underwent massive renovations in recent times, revealing their updated looks in the summer. If you haven’t yet revisited these two historic Los Angeles hotels, here’s what you’re missing.

The Mayfair

Westlake’s The Mayfair was designed by Curlett and Beelman, the same architect duo behind the Culver Hotel. When the hotel opened, its 14 stories made it the tallest building in the west—today, the Wilshire Grand holds the title, thanks to its decorative spire. The Mayfair does have a 15th floor but, like many American hotels, is missing its unlucky 13th.

According to Nathalie Fintzi-Gibson, the hotel’s director of sales and marketing, the last time the Mayfair got an upgrade was prior to the 1984 Summer Olympics, which Los Angeles hosted. Designer Gulla Jónsdóttir handled the renovations, bridging modern details with elements of the hotel’s past. For instance, cube-shaped chandeliers in the spacious lobby are cut to cast patterned shadows upwards, recreating details found in the original tin and copper tile ceiling. The focal point of the lobby is a white sculpture behind the bar, visible from the street when the doors are flung open. The piece is known as the Mayfair Flower and is meant to remind the viewer of the hotel’s Jazz Age roots.

Other historical details in the guardrails that line the mezzanine; they reflect design elements from the hotel’s exterior. It’s also where you’ll also find a peaceful seating area around an olive tree. Some of the guest rooms pay homage to the past with a 1929 map of Los Angeles printed on their walls. The hotel appears in a cut-out, alongside Westlake Park and Elks Temple. Elks Temple, once known as the Park Plaza Hotel and today as The MacArthur, was another Curtlett and Beelman project.

While Hollywood’s Hotel Roosevelt would host the first Academy Awards in 1929, it was The Mayfair’s ballroom where the stars converged for an afterparty. Today, the renovated ballroom boasts a vapor fireplace and an 800-crystal chandelier.

Elsewhere, Old Hollywood glam is eschewed in favor of hard-boiled detective fiction. It is said that author Raymond Chandler stayed at The Mayfair in the late ’30s while writing the short story “I’ll Be Waiting.” As the story goes, Tony Reseck is the “house detective” for the 14-story Windermere Hotel. He soon encounters a young, red-haired woman named Eve Cressy who’s been staying at the hotel for five days, awaiting the return of her ex-con husband. She sits alone in the hotel’s communal radio room, listening to music in the wee hours of the morning. Reseck soon finds that Eve is involved in a caper, and so is his own mobster brother, Al.

This story is where the Mayfair’s contemporary restaurant, Eve American Bistro, derives its name. The hotel’s private dining room bears Chandler’s name, and two suites—the Vivian and the Marlowe—are named for other Chandler characters.

The Mayfair, akin to the fictional Windermere, once had something of a radio room. Fintzi-Gibson said in the 1930s, there was a live broadcast that took place out of the hotel. The Mayfair offers a modern take on that concept with a glass-enclosed podcast room, which can be rented out and used to record shows.

Dining options include the aforementioned Eve, helmed by chef Scott Commings, serving lunch, dinner, and brunch on the weekends. A porthole fireplace allows people to peer from Eve into the lobby or vice verse.

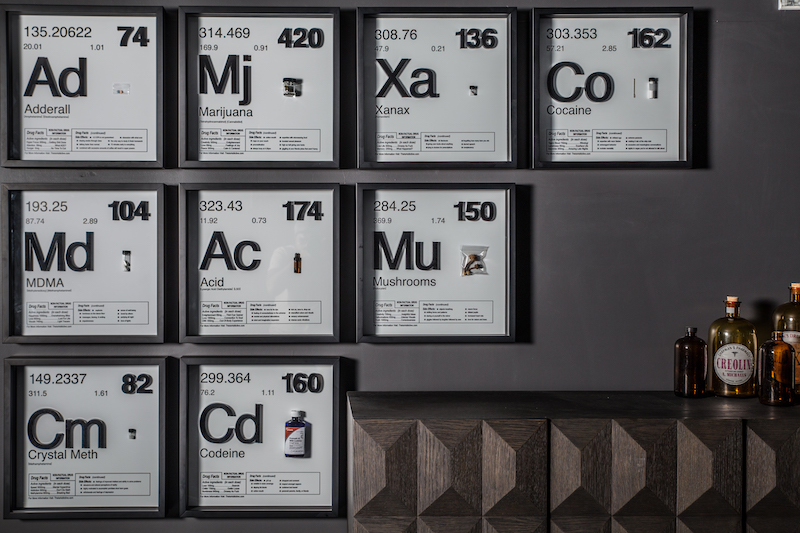

The ground floor also features Chicago-based coffeeshop Fairgrounds. This is the chain’s first West Coast location. They open at 6 a.m. daily for breakfast items, coffee, and tea. The usual suspects are on the menu, but so is a matcha and espresso bar, and a list of espresso- and tea-based “elixirs,” including an espresso old fashioned with walnut bitters. There’s no booze in these; for that, you could head to the M Bar in the lobby, or, behind M Bar, the sultrier, darker Library Bar. Here, you’ll find a collection of artworks, including Daniel Cohen’s “Periodic Table of Drugs,” in which a number of illicit substances are framed like, well, a periodic table. The piece somewhat ties into the hotel’s cheeky mantra.

“The hotel tagline is ‘a hotel under the influence,’ which we leave up to your interpretation,” Fintzi-Gibson explains. “Art, food, music, beverage, whatever that may be.”

For additional art, the Mayfair brought on Kelly “RISK” Graval as the hotel’s artist-in-residence and curator. Graval’s work can be found alongside artists including Patricia Torkan, Jason REVOK, Shepard Fairey, Joey Colombo, Geoff Melville, and Alex “Defer” Kizu. It’s definitely worth a stroll through the hotel’s common areas to see the art, and it’s worth listening, too. The music has been curated by talent collective Regime 72, and that includes performances and DJs that take place at the hotel, as well as the daily and nightly playlists.

Future plans include the addition of a swimming pool to the third floor of the parking structure.

Hotel Figueroa

Craig Robertson, author of The Passport in America, told National Geographic that it was highly uncommon for women to travel by themselves in the 1920s. And married women could only get passports in their husband’s name, e.g. “Mrs. John Doe.” Traveling solo was even harder for women of color.

Downtown’s Hotel Figueroa was built by the YWCA as a safe place for women traveling alone to lay their heads. Men could only stay at the hotel if they were with their families, and only then on designated floors. According to Marketing Manager Natalie Terceman, the hotel, at a cost of $1.25 million, was then the “largest project funded, owned, operated, and managed by women—and it was for women.”

The hotel’s first manager—and the first female hotel manager in the nation—was certifiable badass Maude N. Bouldin, who is depicted atop a motorcycle in a red-washed painting by artist Alison Van Pelt that hangs near the concierge. Under Bouldin and the other women who ran the property, the hotel bustled with social activity. It offered a writing salon, art exhibitions, musical performances, and lectures on social justice.

The YWCA would lose the hotel following the stock market crash of 1929, though they would keep their headquarters on the property through 1951. The hotel remained operational and continued to serve both women travelers and locals looking for art and lectures for the next several decades.

Following a period of decline in the ’60s and ’70s, Swedish entrepreneur Uno Thimansson purchased the hotel in 1976 and gave it a Moroccan makeover. The hotel remained this way for over 30 years until it was purchased by Brad Hall in 2014, with the most recent renovations taking place from 2016 through this past summer. Today, one can only find Moroccan vibes in the lower level space, Tangier, which is available for private events.

The renovation comes courtesy of Santa Monica-based design agency Studio Collective, and accounts for the entire property. The new lobby is posh, yet offers a homey feel, with plenty of comfortable chairs and sofas to tuck away in with a cup of the hotel’s fig tea or a cocktail.

At the lobby bar, guests can choose among a number of bespoke gin and tonics or “gintonicos,” each one infused with fruits, spices, and botanicals. Throughout the hotel, these and other cocktails were programmed by Dushan Zaric, the man behind the cocktails at West Hollywood’s Employees Only. For food, there’s restaurant Breva, helmed by chef Casey Lane, and specializing in Basque and Mediterranean-style fare.

Should one require sun, a stroll down a short hall lined with L.A. street scenes shot by photographer Estevan Oriol will lead to the pool. It’s coffin-shaped, and no one knows why. It’s flanked by two bars: the breezy Veranda, where one can order flatbreads, salads, and mains; and Rick’s, where tropical, poolside-appropriate cocktails are served.

Yet another bar, Bar Alta, will open in December. It’s a hidden, 28-seat cocktail lounge, accessible via reservation only.

“The drinks are not served over the bar. The bartender comes around and serves you,” Terceman said of the concept. “It’s a more engaging experience. There will always be five classic cocktails, and then whatever [Zaric] creates from there.”

There’s one way to access Bar Alta that’s particularly fun. The Casablanca Suite features a secret private dining room, Casbah, that one finds behind a bookcase by pressing the correct spine. Casbah contains one possible entrance to Bar Alta, for those who need to be as clandestine as possible.

Finally, if you’re looking for a scavenger hunt, try to find all the triangles. The triangle symbol associated with the YWCA can be found in several places, including the exterior of the building, over the fireplace in the Gran Sala event space, and hanging over the lobby entrance. While you’re looking, you’ll get a chance to see the hotel’s art collection, specifically curated with women artists in mind, including Lily Stockman, America Martin, and Alexandra Grant.

Juliet Bennett Rylah is the Editor in Chief of We Like L.A. Before that, she was a senior editor with LAist and a freelancer for outlets including The Hollywood Reporter, Playboy, Los Angeles Magazine, IGN, Nerdist, Thrillist, Vice, and others.