Handprints on a sidewalk. Chalk art on a bridge. Murals on the concrete channel of the Los Angeles River. The physical marks that Angelenos leave on their city come big and small. They are as varied in medium as they are in message. You might pass by dozens of examples everyday and not even realize it. For some, it’s just white noise, inconsequential b-roll playing during the intermissions of our lives, and we can dismiss these images as easily as we can see them. But should we? Sometimes, it turns out, the simple act of scrawling creates a strand that connects a culture through its history.

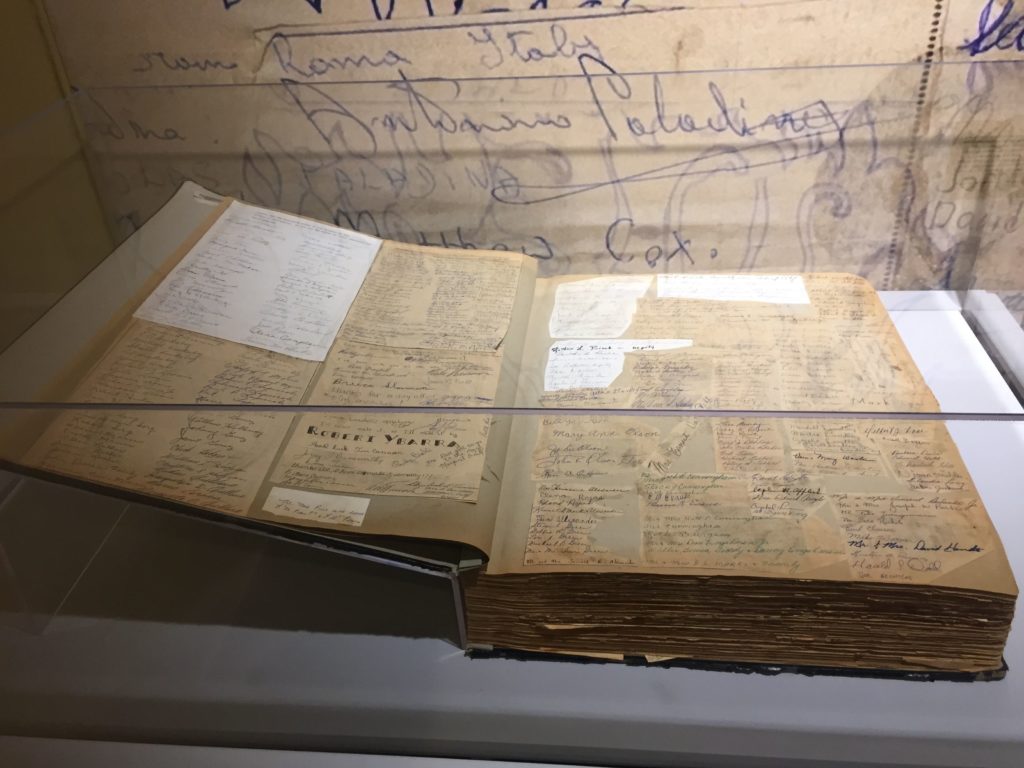

Consider The Los Angeles Public Library’s autograph collection. The collection began in 1905 when city librarian Charles Lummis mailed specially designed LAPL stationary to many of the era’s most important figures, “People Who Count” according to Lummis, with the instructions to “Improve upon this page.” The intention was to help put Los Angeles, then a relatively small town, on the map.

If famous folk were sending the library their autograph, then the city, its library (and by extension, the notorious celebrity-chasing Lummis) must also be important. Recipients of Lummis’ stationary, including conservationist John Muir, The Wizard of Oz author L. Frank Baum, and social reformer Jane Addams, returned the paper to the library with not just their autograph, but also art, poetry, and more.

Since then, the library’s autograph collection has expanded to include autograph books, baseball cards and even a giant book compiled in 1969 by radio station KLAC consisting of Angelenos’ autographs congratulating the Apollo 11 astronauts.

In his new book The Autograph Book of Los Angeles, USC professor and native Angeleno Josh Kun uses the autograph collection to shine a light on not just the library’s collection, but the other ways people have written themselves into civic memory. The Autograph Book is the third book in a trilogy that Kun has written in collaboration with the Los Angeles Public Library. His three books have used the library’s special collections to explore the history of Los Angeles, with the first two focusing on the library’s sheet music and restaurant menus. For his third and final volume in the series, Kun had plenty of options among the library’s collections, including film and bullfighting posters, but the library’s century old autograph collection seemed like the perfect choice.

In preparation for The Autograph Book of Los Angeles, the library recreated Lummis’ original autograph stationary and held autograph days at branch libraries, allowing Angelenos both renowned and unknown to add their signature to the collection. If Lummis’ idea was for the autograph collection to be full of “People Who Count,” then the expansion of the collection also expanded the definition of who counted and whose signature matters; be it billboard legend Angelyne, the staff of Los Feliz taco spot Yuca’s, or Chatsworth resident David Gurnick, who wrote “I would just like to be a part of it” next to his signature.

The great twist of The Autograph Book is that while it starts with autographs written on paper, it shifts into other forms of writing, primarily graffiti. When Kun was pitching the book to the library, he realized “it’s not autographs, it’s about collecting names to say something about a city and about leaving a mark,” Kun tells We Like L.A. As Kun points out in the book, the library’s collection includes an 1873 photograph of names carved into a door at a Civil War era military outpost near the Port of L.A., quite possibly the oldest graffiti in the L.A. area.

Kun uses the library’s historical photos of graffiti, graffiti abatement, and the legal graffiti of the famed forecourt at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre as a way of exploring how autographs exist beyond the page. The Autograph Book also contains essays by acclaimed artist Chaz Bojórquez and Susan Phillips, author of the recently released The City Beneath: A Century of Los Angeles Graffiti.

Phillips, a Torrance-born professor at Pitzer College, has a long interest in graffiti studies and began photographing tags in the early 1990s. She had come to graffiti by accident while living in Carson. “I was interested in art that had an intrinsic connection to social life and I just didn’t see it in our society,” Phillips tells We Like L.A. After thinking about if it was mediums like movies or advertising, it eventually hit her that graffiti was that medium.

While she was familiar with gang graffiti, it took Phillips time to learn about Los Angeles’ general graffiti history. In the late 1990s, while working on a pre-doctoral fellowship on gang graffiti at the Getty Research Institute, Phillips gave a presentation on graffiti. But when a historian asked her about the history of graffiti in Los Angeles she said it didn’t exist. “There’s nothing left, it’s all been erased, you’d be lucky to find something from 1975,” Phillips recalls saying. Within weeks of that statement, Phillips discovered a piece of graffiti from 1931 under the Spring Street Bridge and realized “I just hadn’t been looking in the right place or at the right scale. I had been looking big, not these tiny writings in pencil.” Soon after Phillips, joined by Bojórquez and other friends, began hunting for graffiti everywhere around Los Angeles.

In 2000, while researching her first book, Wallbangin’: Graffiti and Gangs in L.A., Phillips discovered 20 pieces of hobo graffiti in grease-pencil under the San Fernando Road Bridge in Pacoima including the “monica” (hobo slang for someone’s hobo name or “moniker”) of the legendary “kings of the hobos” A-No. 1, dated 1914. While there’s no guarantee that it was the work of the real A-No. 1 (his fame meant he was often impersonated), it became clear to Phillips that this was the oldest graffiti in the city limits.

Though she originally envisioned The City Beneath as a book of photographs, the five years of researching and documenting graffiti pieces caused Phillips to refocus the book on the often-marginalized people who created them. The City Beneath explores locations ranging from storm drain tunnels in Highland Park to the rafters of movie studios to explore power, labor politics, sex, coming of age and more. It all comes back to Phillips’ understanding of graffiti as an art form connected to social life: Gangs and surfers using graffiti to mark their territory, closeted gay men of the 1920s writing both lewd and loving graffiti messages seeking partnership, seafarers writing on the docks of the Port of L.A. to complain about bosses or break up the drudgery of their long downtimes. As she writes in The City Beneath, “seen through the writing on its surface, the city’s infrastructure seems less like an archive of power and more like a witness to people, texture, and community.”

When Phillips made the knowledge of the hobo graffiti public in 2016, it was met with celebration as there are few surviving examples of hobo graffiti in the country. Kun tells We Like L.A. that the hobo graffiti was one part of the pitch he made for The Autograph Book. According to Kun, he told the city librarian “Isn’t it interesting the city is getting excited about the hobo graffiti, but are whitewashing other graffiti? Whose markings are celebrated and whose are demonized?” At that point, he says, the librarian fully understood the project.

In their books, Kun and Phillips draw attention to the how the act of signing is a form of immortality, a moment in time and place now frozen in public view. In The City Beneath, Phillips takes two women to Pasadena’s Holly Street Bridge to see where their father and grandfather had left their names decades ago in chalk and pencil that are still visible on the bridge. While in his essay in The Autograph Book, Bojórquez discusses how painting his tag on walls gave him the same feeling as when he’d trace the signatures of celebrities at the Chinese Theatre. “It makes you known, makes you immortal, makes you think you can last forever. It empowers you,” writes Bojórquez.

Both The Autograph Book and The City Beneath come at a time when Los Angeles is starting to better appreciate its graffiti history. Graffiti and street art have gone into galleries with MOCA’s 2011 Art In The Streets exhibit, and Art In The Streets co-organizer Roger Gastman’s 2018 independent exhibition Beyond The Streets. In mid-November, the L.A. Clippers donned jerseys designed by local graffiti legend Mister Cartoon with the name Los Angeles done in the old English script popular in cholo graffiti. According to Phillips, this sea change is long overdue. “Outside of Los Angeles, L.A. graffiti, especially from 1970s gang culture, is completely valorized. It’s considered one of the great graphic traditions in the world,” says Philips.

Graffiti culture has also found its way into the mainstream in surprising ways. When Kun first pitched The Autograph Book, he pointed out that while most Angelenos might not be throwing their name up on walls, they’re still tagging. “Every teenager in contemporary Los Angeles are tagging people in posts on social media,” says Kun. While he can’t point to etymological connection between the two meanings of “tagging,” he says the ideas are similar. “You’re trying to establish your connection to someone else and to a community, or trying to get someone more famous to look at your work,” he added.

Kun hopes that their books will help people better understand Los Angeles as “an ever-evolving encyclopedia of names and marks. An urban index of who has been here and who is still here.”

Phillips echoes that sentiment, “The city is a custodian of its own history. It almost has a life beyond people and is an inadvertent collector of a history that you have to develop the eyes to see it. What I try to do is try to develop my eyes so I can share these stories with others, even though it’s a partial vision.” The most important thing, both authors agree, is that Los Angeles is pulsing with life, and, according to Phillips “you need to crack it open to let those voices out instead of just suppressing them.”

The Autograph Book of L.A. exhibit at Central Library will be on display at the first floor galleries through January 19, 2020.